The plays of Jonas Vaitkus are “studies in the evil that pervades history, man and the world around him.” So wrote theatre critic Rūta Vanagaitė in 1984, formulating the director’s main theme and defining the conflictual essence of his relationship with time. Rūta Vanagaitė, „Kaligula“: variantai“, Literatūra ir menas, 1984-03-03, p. 6. The exclusive “politicism” of Vaitkus’ theatre and his reputation as the strongest critic of reality and a troublemaker was established by his loud, courageous and artistically strong pronouncement of a diagnosis of universal – political, social, spiritual, existential – shortcomings.

Vaitkus’ “studies in evil” at the Kaunas Drama Theatre had their own kind of ideological counterweight. Gytis Padegimas, who started his career in Kaunas at the start of the 1980s, created a cozy, sensitive, poetically sorrowful and uniquely romantic illusion of the world with his best productions: August Strindberg’s Creditors (1981), Thornton Wilder’s Our Town (1982) and The Long Christmas Dinner (1986) which, with the middle word omitted, was performed first not at the theatre itself, but at the Kaunas Artists’ Hall, and later in the Kaunas City Hall and elsewhere. The play only became part of the repertoire of the Kaunas Drama Theatre in 1991.

This diagnosis, first delivered by Vaitkus in his work in the second half of the 1970s, was developed to its full potential in his plays of the 1980s which – as if in opposition to Nekrošius’ theatrical delving into the ontology of the social outcast – explored the phenomenon of government, drawing various diagrams of the relationships between leaders, leader-monsters, society and the dull masses. Vaitkus spoke out most strongly along these lines in 1982, when he dared to stage a grotesque, even “Ubu-like” but uniquely dramatic production, full of double effect and double meaning, based on Mikhail Shatrov’s Leninist play Blue Horses on Red Grass about the depravity of the Soviet system (with artistic design by Janina Malinauskaitė and composition by Vidmantas Bartulis).

In his production of Blue Horses, Vaitkus seemingly united the satire of Ubu the King with the drama of Šarūnas: chastushka songs about free love rang out, a huge doll of the Proletariat strolled around the stage declaring proletarian cult slogans that it itself could not understand, etc. And sitting on a white armchair downstage from all of this noise was Lenin (played by Juozas Budraitis), free of makeup, speaking in a strange falsetto, and somehow strangely distorted – handicapped by paralysis, he was but a tragicomic remnant of the revolutionary leader, a kind of amalgamation of several associations: “a Leonid Brezhnev still in control of a stagnant country, and a bound Prometheus punished for his theft of fire.” Audronė Girdzijauskaitė, „Kauno valstybinis dramos teatras“, in: Lietuvių teatro istorija. Kn. 4: 1980–1990, sudarė Irena Aleksaitė, Vilnius: Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno institutas, 2009, p. 172.

The ruling Soviet institutions remained silent after Blue Horses. In truth, as the Kaunas Drama Theatre prepared for a tour of Moscow in 1983, the Ministry of Culture pressed the theatre not to include the play in its traveling repertoire. Nonetheless, soon after the staging of his own Literatūros pamokos (Literature Lessons) in 1985, Vaitkus was made to pay for the “sins” of Blue Horses. Egged on by teachers, a fierce campaign accusing him of his “anti-child” activities began.

On the one hand, Vaitkus expanded upon the theme of a leader consumed and destroyed by power by strengthening its dramatic effect and, on the other hand, by intensifying its strangeness and theatricality, delving into ever more intense experiments in the fluidity of stage imagery.

This was demonstrated in a 1983 production of Albert Camus’ Caligula (artistic design by Vitalijus Lenickis, stage movement consulting by Grigorijus Gladinas) in which the story of the dramatic self-destruction of one leader (a demonic rebel and capricious, slightly pathological lad) unfolded in an emphatically theatrical space full of strange characters (among them a dwarf) – “crawling, obscene, cowardly little beings convulsively clinging to life”. Egmontas Jansonas, „Kaligula“: variantai“, Literatūra ir menas, 1984-03-03, p. 6.

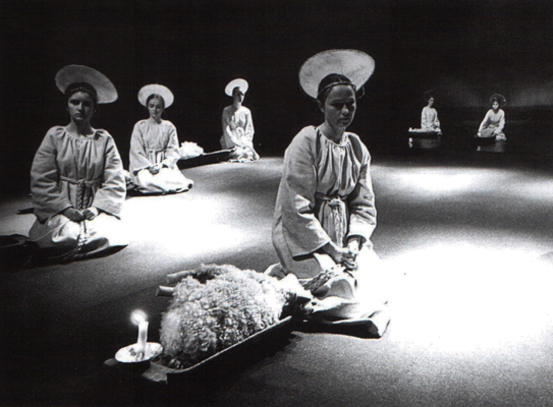

This theme took on an even more theatrical form at the end of 1985, in a production of Shakespeare’s Richard II (artistic design by Dalia Mataitienė, composition by Šarūnas Nakas) that rocked the Kaunas Drama Theatre. As a foreign theatre critic described the production after seeing it performed at a Shakespeare festival in Weimar, Germany in 1988, Janet Savin, „Plays in the Second History Cycle in Bohemian and Lithuanian Theatres“, Shakespeare Bulletin, 1988 09/10–11/12, p. 42. Vaitkus spoke – focusing in particular on the “expression itself" – about the eternal “comedy of government” in which “one comedian (Budraitis’ Richard II) was always simply replaced by another (Viktoras Šinkariukas' Bolingbroke)" Egmontas Jansonas, „Spektaklį reikėtų suvokti“, Komjaunimo tiesa, 1986-02-28, p. 3. who inevitably compromised himself. The director sought to express and visually portray the coldness and lifelessness of the inertia of the history of power, stylizing the expression of monumental tragedy and creating severe, rational and symmetrical interludes inhabited by sculpturesque, larger than life, heavy and slow moving characters with face masks of exaggerated features, bathing the stage in red light reminiscent of stagnant blood.

Comments

Write a comment