The post-war Lithuanian glass industry was stagnating: it employed no professional artists and glass craftsmen at the various workshops were not blowing or casting any unique pieces. Only a few artists were designing artistic glass pieces, partially satisfying the demand for such work and drawing attention to a vital field of art, full of plasticity and opportunity.

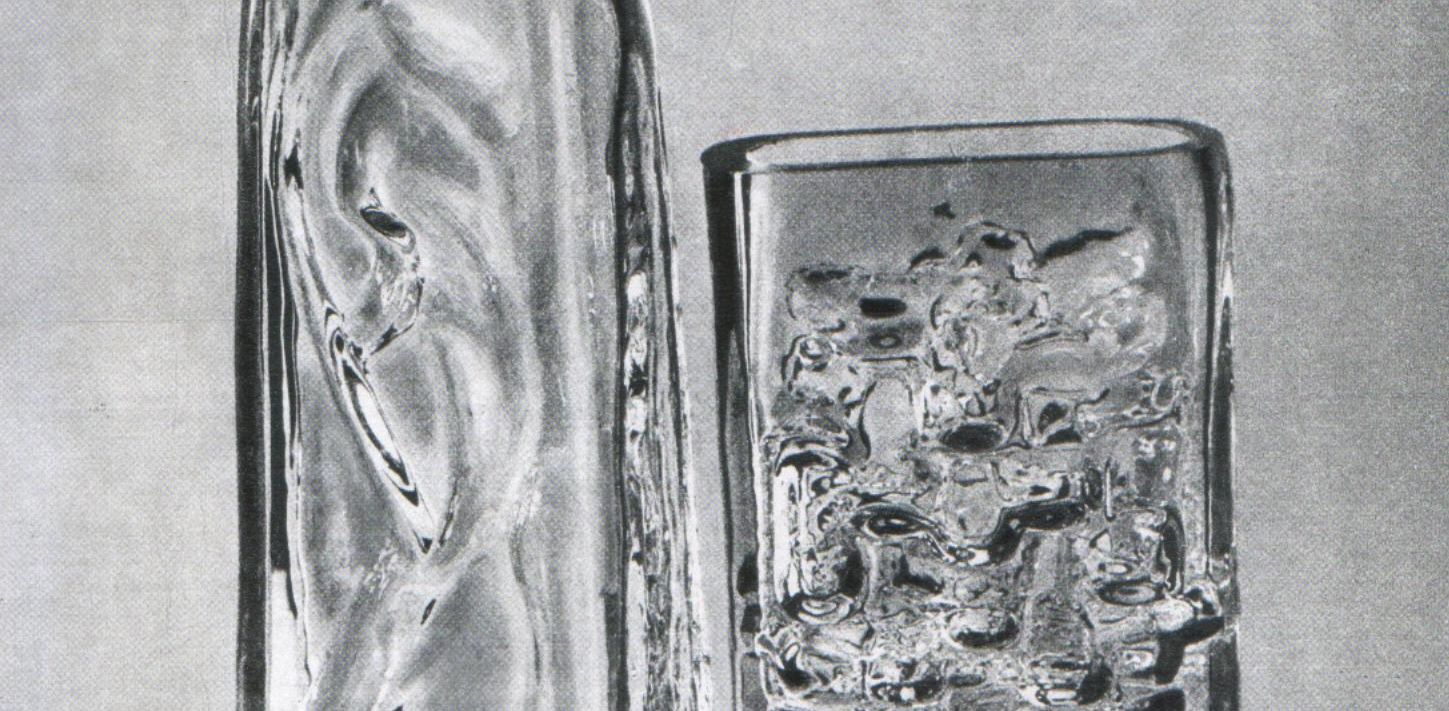

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974), already known for his work in the inter-war period, was forced by circumstance and a loss of commissions to begin experimenting at the Aleksotas glass factory, where he set up his own small workshop equipped with a small, liquid fuel-fired furnace. There, he created low-fire fine glass works: vases, plates, aquarium bowls, lamps, and small glass figurines. His colorless glass dishware was blown by J. Zapolskis and S. Bagdonavičius, glassmiths at the Aleksotas factory. The range of shapes of the dishware was limited by the inferior quality of the available glass that was unsuitable for fine art designs. Ušinskas decorated his creations using stained glass painting techniques: employing silicate paints (glazes), enamels, metal film, gilding and silver plating. Flaws in the furnace's construction often led to contamination of the molten glass, but glazing would usually cover up shoddy glass. Initially, Ušinskas used the supply of paints that he had brought with him from Paris, and later turned to mixing his own glazes.

Ušinskas' decorative vessels were smoothy shaped, with distinct contours and harmonious proportions. The ornamentation applied to the pieces served as the main decorative accent, as if continuing the style of the stained glass work from the artist's pre-war creative period. Ušinskas sought to obtain the glow of colors seen in stained glass through his stylized, constructive design compositions, but he did not overuse coloring, believing that ancient artisans were capable of creating many tones and shades from one basic color. Kazys Strazdas, Lietuvos stiklas: nuo 1940 metų, Kaunas: Technologija, 1997, p. 122. Examples of such work include Mėnuo saulužę vedė (The Moon Married the Sun, 1957), Klumpakojis (1959), Eglė žalčių karalienė (Eglė - Queen of the Serpents, 1960), Sportininkai (Athletes, 1962), and others that displayed hints of the festival style.

As he worked at the Aleksotas glass factory, Stasys Ušinskas was assisted by his student and sister, Filomena Ušinskaitė, whose contribution to Lithuanian glass art has not yet been sufficiently appreciated. The creative style of Ušinskaitė, who trained as a stained glass artist and theatre set decorator, approximated that of her brother. The similarities of her vases created in the 1950s and 1960s to the fine glass work designed by Stasys Ušinskas were not only the result of their using similar technology, but were also a factor of her brother's strong, lifelong influence over her. Both artists sought to master and improve glassworking techniques. To this day, specialists still sometimes argue over which of the two artists created a given piece of glass.

Ušinskaitė's tall, monumental vases, blown by the Aleksotas glassmiths, did not vary much in shape because she needed to leave as much flat surface as possible for ornamentation, the most important artistic accent of her pieces. She painted her vases using a technique introduced by her brother Stasys, using glazing and enamels with gold and silver highlighting. Though the themes featured in her decoration also had to bow to the demands of the time period, and while Ušinskaitė did create works depicting scenes broadly popular in Soviet art such as collective farm life and the pursuit of international peace (see Fermoje (On the Farm, 1960] and Taika [Peace, 1961]), her works were not illustrative in nature and they adhered to the specific characteristics of decorative art.

From the end of the 1950s, glass art designs were also being created by Stasys Ušinskas' students: his second wife Vitalija Blažytė (1926–1999), and, later, his two daughters from his first marriage, architect Vida Ušinskaitė (1936–1976) and glass designer Jūratė Ušinskaitė (1936–1996?). All of them further developed the glasswork traditions established by Ušinskas himself, creating vases of monumental form and expressive decoration. It was entirely natural that the whole family became caught up in the pursuit of fine glass design, as all of the women were strongly influenced by Ušinskas' authority on the subject.

|

Read more: Stasys Ušinskas.

|

Comments

Write a comment