In the Soviet context, the word "design" had a very specific meaning. Use of term was usually avoided because of its "capitalist" undertones and its incongruity with socialist ideology:

The ideas and methods used by competing capitalist firms are alien to us – their camouflaging of a product's deficiencies with an effective use of gilding, ostentatious form, or the sublime combination of colors. Algimantas Bielskis, „Gaminys ir vartotojas“, Mokslas ir technika, 1965, Nr. 12, p. 8.

Though the ideals of socialist planned economies were fundamentally different from the Western understanding of design, this didn't mean that there was no design, or designers, to speak of. On the contrary, many events that were critically important for Soviet and Lithuanian design occurred in the late 1950s and early 1960s, including the establishment of new institutions, the launch of specialized study programs, the organizing of the first design exhibitions, and the evolution of concepts concerning the modernization of objects and environments.

To gain a better understanding of this period, we need to introduce different keywords that better reflect the realities of the day. Though professionals used the English-derived term "dizainas" (design), in official discourse the concept was always being modified into new and awkward terminology: industrial art (pramoninė dailė), industrial or technical aesthetics (pramoninė arba techninė estetika), artistic construction (meninis konstravimas), or industrial modeling (pramoninis modeliavimas). Design was a field that existed between industrial production and applied art and between the technical and the aesthetics, characterized by the contradictions between theory and practice, modern unique projects and manufacturing defects, between professional mastery and simple hackwork, and between declared prosperity and perpetual shortage.

People who worked in this specific field were usually called "industrial product modelers", "artists-constructors", or "artists-decorators" – and only very rarely as simply "designers":

Our mission as artists-constructors is to create objects that satisfy the needs of the members of our socialist society, to help them strengthen the shape of our communist life. Nijolė Tumėnienė, „Technika ir menas“, Mokslas ir technika, 1968, Nr. 8, p. 24.

We could list more than a hundred Lithuanian designers who began their creative careers in the late 1950s and 1960s – some well known, others completely unknown. Some specialized in a specific area of design (in furniture, computing or branding, for example) and dedicated their entire professional careers to that field, while others spent only a few years in design, usually after receiving a specific job appointment after graduation or, in rare cases, by taking on a commission of an applied nature (as in the examples of painters such as Algirdas Petrulis and Eugenijus Antanas Cukermanas).

Responding to the need for new specialists, the Vilnius Art Institute introduced a new field of specialization in design in 1961, or rather, to quote source materials from that time, it "introduced the specialization profiles of artistic industrial modeling and decoration," and later opened the Department of Industrial Artistic Construction, headed for several decades by Professor Feliksas Daukantas (1915–1995), considered the pioneer of Lithuanian design education.

The design studies program was noted for its highly praised introductory course based on the Bauhaus BauhausThe Bauhaus was an architectural and design school that operated in Germany from 1919 to 1933 and profoundly influenced the understanding and later development of design.

The Bauhaus school program advocated the rejection of classification into "fine" and "applied arts" and instead promoted a combined approach to theoretical fundamentals, art, crafts and industrial production technologies. Over the course of its existence, the school was led by renowned architects such as Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and hosted lectures by such famous European modernists as Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Max Bill, among others.

One Lithuanian was among the 1,250 students who trained at the Bauhaus school – the engineer Vladas Švipas (1900–1965), whose professional career is associated with modernist architectural and urban development intiatives undertaken in the inter-war period in Kaunas, including the activities of the Chamber of Agriculture's Construction Department.

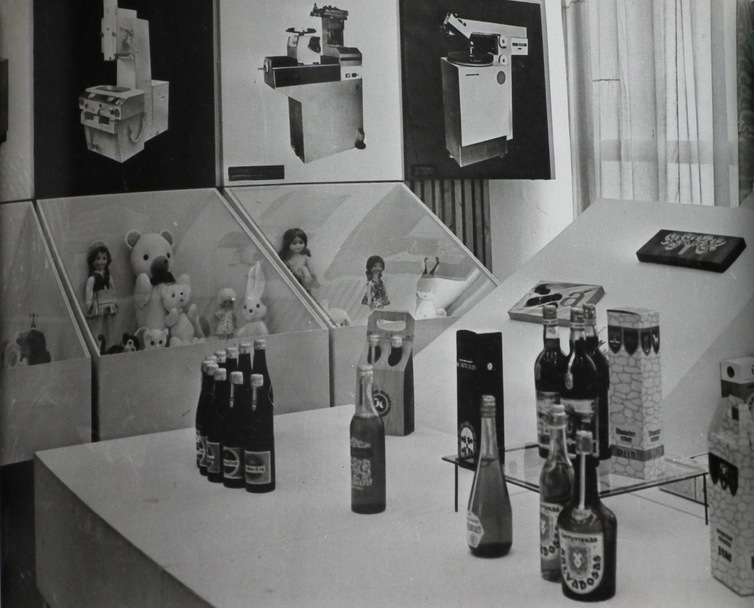

method, as well as for contract agreements with producers and a diversity of activity genres and fields of work in pursuit of original and contemporary forms and functional solutions for a wide array of different objects: welding equipment, machinery, the entire transportation system, household chemical packaging, beer bottles, and new trademarks.

The Bauhaus school program advocated the rejection of classification into "fine" and "applied arts" and instead promoted a combined approach to theoretical fundamentals, art, crafts and industrial production technologies. Over the course of its existence, the school was led by renowned architects such as Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and hosted lectures by such famous European modernists as Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Max Bill, among others.

One Lithuanian was among the 1,250 students who trained at the Bauhaus school – the engineer Vladas Švipas (1900–1965), whose professional career is associated with modernist architectural and urban development intiatives undertaken in the inter-war period in Kaunas, including the activities of the Chamber of Agriculture's Construction Department.

method, as well as for contract agreements with producers and a diversity of activity genres and fields of work in pursuit of original and contemporary forms and functional solutions for a wide array of different objects: welding equipment, machinery, the entire transportation system, household chemical packaging, beer bottles, and new trademarks.

Training designers is something new. It needs support - support for experimentation and the pursuit of new approaches and a trust in the courage and hopes of those who experiment. К. Кантор, „Начатки дизайнерсково образования“, Декоративное искусство СССР, 1965, Nr. 4, p. 27.

137 students graduated from the design department between 1965 and 1980 - an average of seven graduates per year. Some designers were given full-time positions with enterprises (like Algis Šarka, from the first graduating class, who spent his entire life working for the Sigma Computing Machine factory in Vilnius), but most worked in specialized design offices.

Comments

Write a comment