The 1980s were a significant period in the history of Lithuanian ballet not only for the new productions staged that decade, but also for the clearly evident divide that had developed between classical ballet and contemporary choreography. A deliberate exploration of new, fluid forms began, departing from the canons of classical ballet and emphasizing creative individuality as the most important artistic quality. Of particular importance during this period was the emergence of new opportunities for Lithuanian ballet and solo artists to organize international tours, allowing both soloists and entire companies to break out of their previously restricted environment and benefit from a more comprehensive and diverse reception by audiences and professionals alike.

As before, the Lithuanian Opera and Ballet theatre planned its season according to repertoires outlined in advance. A list of recommended pieces and productions was usually prepared and circulated, including sixteen ballets written by composers from the various Soviet republics. These ballets featured productions with diverse storylines, some based on legends rooted in the folklore of the numerous Soviet nations, while others derived from classical (Dubrovsky, by Valeri Kikta, based on Alexander Pushkin’s novel) or Soviet (The White Steamship, by Alexander Soynikov, based on the novel of the same name by Chingiz Aitmatov) literary works, or Soviet history (Vitaly Kireika’s ballet Sunstone, about the Zhurbin dynasty of mineworkers and, as described in the official list, “the heroic glory of labor in the Donetsk region”, or Yevgeny Stankovich’s ballet Sparks, on historic and revolutionary themes). None of these, with the exception of Antanas Rekašius’ Amžinai gyvi (Eternally Alive), was ever staged in Lithuania.

Toward the end of the 1970s and in the early 1980s, Lithuanian ballet was most profoundly influenced by choreographer Vytautas Brazdylis Vytautas BrazdylisVytautas Brazdylis was born into the family of ballet artist Vytautas Brazdylis Sr., and began studying at the Choreography Department of the M. K. Čiurlionis School of Art in 1960 (under the tutelage of Pranas Peluritis). He studied for three years (until 1966) at the Moscow School of Choreography, and danced with the Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre until 1973. In 1973–1978, Brazdylis attended the Choreography Department of the Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) Conservatory, studying under the renowned late 20th century classical choreographer and Professor Pyotr Gusev, as well as with choreographer Igor Belsky. (b. 1947), who became the ballet company’s senior choreographer in 1980. His first work as lead choreographer was a production of Ludwig Minkus’ Don Quixote in 1978. Though the production’s choreography was based on a version created in the early 20th century by Russian choreographer Alexander Gorsky, Brazdylis sought to smooth out the previous version’s dramaturgical disparities by approaching the production as a choreographic treasure, which is why he staged the final pas de huit based on a version of Don Quixote first mounted at the State Theatre in Kaunas by its former lead choreographer Alexsandra Fyodorova. In his design for this ballet from the classical repetoire, Brazdylis avoided conventionalism and naturalism. One interesting choice was a vision that appeared during the prologue, an interlude from a knight’s novel that emerges from Don Quixote’s imagination while he is reading, portraying a stylized version of the abduction of the story’s heroine. The sets proposed for Don Quixote by designer Henrikas Ciparis featured stylized graphic imagery with Spanish and Moorish architectural motifs, while the battle with windmills was composed using special lighting effects, including projections to create the illusion of approaching or receding windmill outlines.

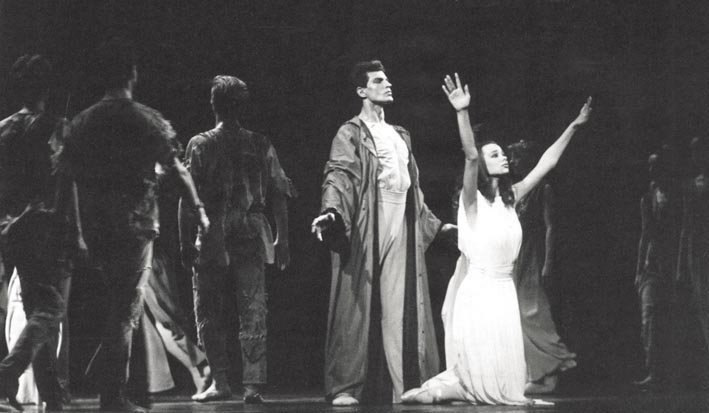

Another Brazdylis production opened in December, 1978—the premier of Juozas Gruodis’ ballet Jūratė ir Kastytis (Jūratė and Kastytis). Due to time constraints, the ballet could not be performed in one single evening. The production did not remain in the company’s repertoire for very long but it did serve to showcase the restraint and lyricism that came to characterize Brazdylis’ work, as well as the choreographer’s pursuit of musicality and a symphonic style.

Brazdylis’ most popular production was his 1979 ballet Baltaragio malūnas (Whitehorn’s Mill)—based on the extremely well-received 1970s musical by Vyacheslav Ganelin—which was later turned into a musical film by Arūnas Žebriūnas under the title Velnio nuotaka (The Devil’s Bride) in 1974. This was the ballet company’s first contemporary production, in all respects—in dramaturgical concept, choreographic plasticity, and set design. It was also likely the first time (not including tours by the company to smaller Lithuanian cities) that a ballet production was performed using a recorded score. The complex choreographic text focused on the characters of Baltaragis (Whitehorn), Pinčukas, and Jurga, using choreography designed by Brazdylis that allowed dancers performing the roles to showcase their acting and dramatic skills. For the first time, Brazdylis and set designer Vytautas Kalinauskas gave audiences a glimpse into the stage wings with all of their technical structures and lighting fixtures revealed, creating the sense of a “production within a production.” Though no continuity of plot was intended, scenes flowed organically from one to the next while minimalist, light sets permitted rapid transition from one setting to another. The ballet’s mournful finale was merely the end of the “production within the production”, as the entire ballet culminated in a musically contrasting, vivid rendition of Léo Delibes’ Coppelia waltz, performed by the entire company. Such a post-modernist approach to ballet dramaturgy was a novelty not just for Lithuanian ballet, but also for Soviet choreography in general. The plasticity of Whitehorn’s Mill was distinguished by organic movement combinations and demi pointe positions. Only scenes depicting visions by the characters Marcelė and Whitehorn were based on classical dance and pointe technique.

After Whitehorn’s Mill, Brazdylis revisited Lithuanian choreography history by working on a new version (premiering in 1980) of his first ballet, Delibes’ Coppelia. Brazdylis presented the comic ballet, usually staged using pantomime, as a more complex psychological drama, with the protagonist forced to choose between reality and his own fantasy (two women—a simple girl named Svanilda and an automated doll by the name of Coppelia.) Although the production ended on a happy note, it was permeated by a gloomy, Hoffmanesque spirit, emphasized by Ciparis’ set designs and costumes.

Such a directorial and visual approach was apparently perceived as being too serious for Delibes’ light music, so a new version of the same ballet was undertaken several years later, with the premiere of a fundamentally changed production opening in 1983. Changes were made to the choreography for the solists while ensemble pieces and dances were arranged on the principle of choreographic symphonism, but the more inventive pantomime scenes were retained. Light and decorative costumes and colorful sets for the production were created by Estonian designer Eldor Renter. The new production proved easy to take on tour: in 1983 the company performed in Kaunas, Alytus, Panevėžys, Šiauliai and other Lithuanian cities, and discussions began over possible tours to Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and Poland. In 1987, Brazdylis was invited to stage Coppelia at the Gdansk Opera and Philharmonic—the first time the choreographer’s work was performed abroad.

Comments

Write a comment