The Soviet government introduced the supervision of art in Lithuania in the first year of occupation. In July, 1940, the new Soviet regime consolidated the various Lithuanian art organisations into one Lithuanian Artists’ Professional Union which, renamed in the spring of 1941 as the LSSR (Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic) Artists’ Union (AU), was placed under the juridiction of the USSR Artists’ Union. As in Nazi Germany, art was henceforth only to be created by members of the Union. The AU became the main tool for the Sovietization of art, organised to effectively control all facets of art production, dissemination and display, not to mention the ideological “training” of artists, government commission and acquisition of artworks, and the organising of exhibitions and press coverage.

In the summer of 1940, the Soviets began implementing their “monumental propaganda plan”, one they had developed in the early days of the Bolshevik revolution, and began destroying monuments built in independent Lithuania, replacing them with new tributes to the Soviet regime. Up to the start of military hostilities between Germany and the USSR, the country’s best artists (Antanas Gudaitis, Justinas Vienožinskis, Petras Kalpokas, Stasys Ušinskas, Juozas Mikėnas, Bronius Pundzius, Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas) worked for the Soviet government, designing posters for elections to the “People’s Parliament” and participating in selection competitions for an exhibition of Lithuanian art planned for the autumn of 1941 in Moscow. Most of the Kaunas artistic community emigrated to the West in the summer of 1944.

The LSSR Artists’ Union resumed its activities in Vilnius as soon as the city was occupied by the Soviet Army, led by Lithuanian artists who had returned from exile in Moscow. The Vilnius Academy of Art was reopened on 24 August 1944. The LSSR Art Foundation was established in January, 1945 and, soon thereafter, presided over newly opened so-called “art workshops” in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda, as well as other enterprises charged with producing artworks and crafts, holiday decorations, stained glass and outdoor sculpture. The first (“Republican”) exhibition of artwork by Lithuanian artists was held at the Vilnius Museum of Art in May, 1945.

Art in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, as in the rest of the Soviet Union and all totalitarian countries, was required to serve the needs of the government’s ideological propaganda and the education of the broad masses. Modernism and neoclassicism were replaced by socialist realism — an artistic method steeped in ideology, requiring artists to adhere to the example set by Russian realists in the 19th century to create realistic depictions of important historical and political figures, events (usually contrived by the ideologues) and “typical” (i.e. desirable, future) facets of life.

This approach was introduced cautiously in the first post-war years since, until 1947, the USSR adhered to a more moderate policy of Sovietising the Baltic countries. Instead of promoting the government-mandated themes of war, rural reform and labour, artists mostly created paintings on more traditional themes. Justinas Vienožinskis painted portraits of writers, composers and cultural figures, while Antanas Žmuidzinavičius and Jonas Šileika crafted sentimental and realistic pieces, and Antanas Gudaitis painted expressively colourful works. For this reason, very few Lithuanian artworks found their way into Union-wide Soviet exhibitions.

During the most brutal period of the Stalinist regime — from the autumn of 1947 to March, 1953 — Lithuania was Sovietised through mass deportations and increasingly severe suppression of various segments of society. Government policy toward artists became extremely rigid. In an address to the Lithuanian Communist Party Congress in 1949, First Secretary Antanas Sniečkus expressed his dissatisfaction with the work of the Artists’ Union and the “overall situation in art”. The fight against expressions of modernism and formalism (the lack of a plot or narrative) began, and the country’s cultural heritage was condemned, particularly the work of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis and the “Ars” expressionist group that had been active in Kaunas in the 1930s.

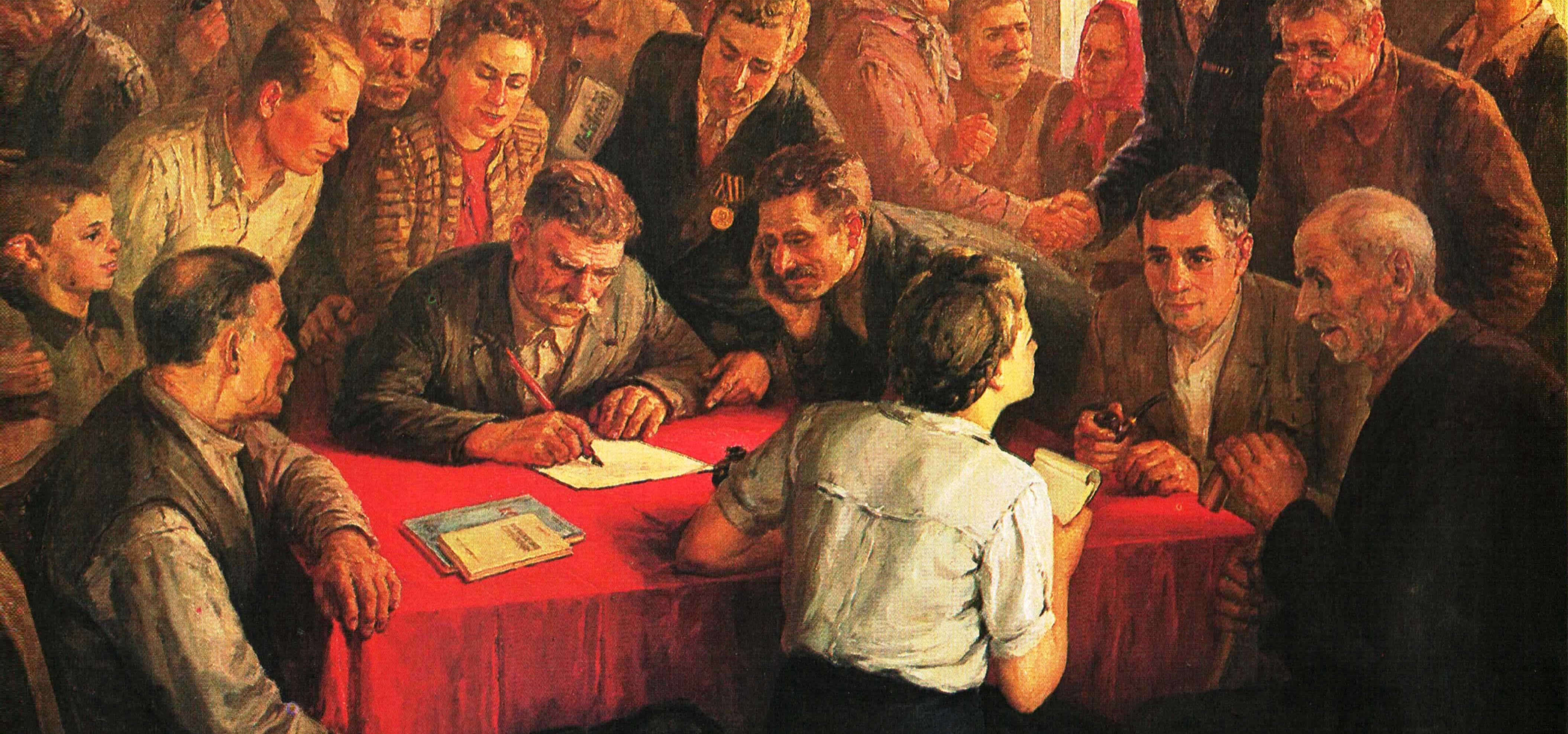

In the Stalinist period, artists created socialist realist paintings featuring multiple figures, such as in Vytautas Mackevičius’ Partizanai (Partisans, 1945) and Liaudies seimo delegacija Kremliuje 1940 m. (The People’s Parliament Delegation in the Kremlin in 1940, completed in 1949), Bronislava Jacevičiūtė’s Salomėja Nėris 16-toje lietuviškoje divizijoje (Salomėja Nėris in the 16th Lithuanian Division, 1951), Kolūkio steigiamasis susirinkimas (Founding Meeting of the Collective Farm, 1950) by Vincas Dilka, V. Mickevičius-Kapsukas ir P. Eidukevičius pogrindžio spaustuvėje 1918 m. (V. Mickevičius-Kapsukas and P. Eidukevičius at an Underground Printing Press in 1918, completed in 1950) by Augustinas Savickas, or a joint work by Antanas Gudaitis and Leonas Katinas in 1949 entitled Svečiuose pas kiaulininkę S. Vitkienę (At the Home of Pig Farmer S. Vitkienė, 1949). A sculpture entitled Pergalė (Victory), by Mikėnas, Pundzius and other artists was unveiled in Kaliningrad (Königsberg) in 1946, while Robertas Antinis Sr. dedicated his sculpture to war hero Mariya Melnik in Druskininkai in 1952. That same year, Vilnius’ Green Bridge was adorned with a group of sculptures: a miner and mason created by Napoleonas Petrulis and Bronius Vyšniauskas, a worker and peasant woman by Petras Vaivada and Bernardas Bučas, two students by Mikėnas ir Juozas Kėdainis, and Soviet soldiers by Pundzius.

In 1956, the ruling Soviet Communist Party condemned the “cult of personality” of the Stalinist dictatorship and its cultural repercussions. Stalin’s successors decided to alter the model of Sovietisation of the Baltic republics in the spring of 1953, realising that repression had been useless: the partisan resistance continued and the Soviet government was still viewed as foreign and temporary. Repression in Lithuania was replaced with a nationalisation policy whose core aim was to incorporate as many Lithuanians as possible into the “construction of socialism”, permitting broader use of the Lithuanian language and a more liberal supervision of culture. The revival of all aspects of culture after 1956 was heavily influenced by the idea promoted by Soviet leaders to transform Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia into the “Soviet West.” For residents of other Soviet regions, Lithuania became the “Little West,” even though most Lithuanians themselves still perceived their own country as an insignificant marginal “republic.” As a result, the gap between actions and words in the management of culture was somewhat wider than in Moscow.

|

See also: Socialist Realism in Literature.

|

Comments

Write a comment