Soviet Lithuanian architecture of the 1960s experienced an optimistic “Thaw” period. After the Soviet leadership’s 1955 decision “On the removal of excess in construction and architecture,” the elaborate and decorative style of Soviet architecture was gradually replaced with “clean” modernism. For some, this meant a conditional liberalization of cultural and art long suppressed by Stalinist Socialist Realism, for others it brought new (but still strictly controlled) ties with the West. Modernism emphasized an optimistic picture of revitalized Soviet life. Though the construction sector viewed this first and foremost from an economic perspective (“faster, cheaper, more”) rather than in terms of aesthetics, architects and artists who yearned for integration into the international modernist community nevertheless began to enjoy real opportunities to bring suppressed ideas to life.

A significant impetus for change came with the Sixth International Youth Festival in Moscow in 1957 and accompanying exhibitions showcasing the visual and applied arts. Until then, the youngest Soviet generation had never seen contemporary Western art. The dissemination of modernism was further aided by the launch that same year of the magazine Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR (Decorative Art of the USSR), which featured reporting from abroad and advocated the modernization of domestic and public spaces.

The stimulus for all of this change came from a program with the lofty title “Art for Everyday Life.” The design of applied artwork (ceramics, textiles, leather, metal) was designated a priority field of art, accelerating the introduction of modernist design in the Soviet Union and in the Baltic republics in particular.

The “thaw” in the cultural realm was marked not only by the liberalization of artistic expression, but also by a programmatic government concern for the people’s “material and domestic welfare.” This shift was clearly evident in the public sphere (in the mass media, for example). Within the context of the Cold War, a new field of focus – a more visible “domestic front” – emerged alongside the considerable attention already devoted to military readiness and armament. The race against the West to improve the material lives of citizens was meant to demonstrate that everyday Soviet life was just as modern and contemporary as in the West.

The differences between Soviet and Western domestic life became acutely evident with the opening of borders and the Soviet Union’s appearance at Expo ‘58 in Brussels, the first World’s Fair to be held after World War II. The USSR’s backwardness was on display for everyone attending the Expo. In 1959, an American exhibition in Moscow showcasing various domestic technologies and innovations in home appliances only served to further highlight Soviet underdevelopment. After these shows, Moscow began taking measures to modernize both the design of its exhibitions and the domestic life of Soviet citizens overall. This led to the opening of new cafés, cafeterias, stores, cinema houses, recreational facilities and sanatoriums; increased production of contemporary domestic technology products, furniture, and home appliances; and the start of planning for the production of inexpensive mass-produced automobiles.

The main goal, promise, and method of achieving “Khrushchevian prosperity,” however, centered on individual family apartments. A huge shortage of housing throughout the Soviet Union hampered efforts to provide even the most basic conditions for modern life. Moreover, the great majority of urban dwellers were still packed into the notorious “komunalkas” – communal apartments housing several families sharing a common bathroom and kitchen.

To address the problem, more and more architects were sent on organized trips abroad to learn firsthand about modern housing construction methods. Understandably, this usually meant travel to the so-called Socialist countries (Czechoslovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania), but, with the help of the Architect’s Union, a few architects were also able to reach the idealized West (Finland, Sweden, even France and Italy).

Architects were particularly pleased by the liberalization of their own trade publications. The Western architecture that had been cut off by the Iron Curtain became gradually more accessible in the form of glossy photographs printed in foreign architecture magazines. The journal Arkhitektura SSSR (Architecture of the USSR) began including more material from the West and it soon became possible to obtain (though not easily) Czech and Polish trade magazines. In the late 1960s, the Soviets signed an agreement with the legendary French modern architecture magazine L‘Architecture d‘aujourd‘hui (Architecture Today) to begin publishing a Soviet version in Russian.

In Lithuania, developments in architecture were showcased by the local journal Statyba ir architektūra (Construction and Architecture), whose title revealed the priority given to construction. In 1960, the state-run magazine Švyturys began featuring a column dedicated to contemporary architecture titled “Architektas dirba. Ar visada gerai?“ (Architect at work. But is that work always good?). Modernism as a clean, sound, and acceptable style was promoted in Jonas Minkevičius’ books Miestai vakar, šiandien, rytoj (Cities: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 1963), Lietuvos TSR interjerai (Soviet Lithuanian Interiors, 1964) and Naujoji tarybų Lietuvos architektūra (New Soviet Lithuanian Architecture, 1964).

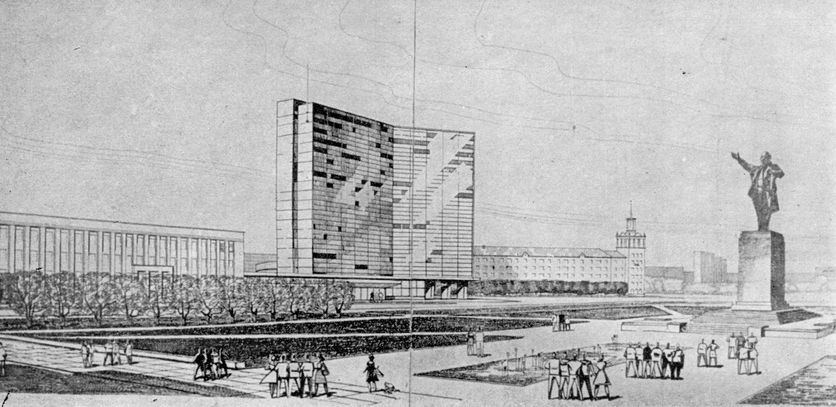

It quickly became clear that the liberalization underway was conditional and that many innovations were purely superficial. Nevertheless, a new generation of Lithuanian architects born in the 1930s and educated in the mid to late 1950s used their talent and connections to place themselves at the epicenter of architectural change and even began to dictate new styles. Having broken away from the architectural concepts dictated by Socialist Realism, they capitalized on the modernism of inter-war Lithuania and their experience with the West (primarily Scandinavia) and, together with architects in Estonia and Latvia, began shaping the image of Baltic modernism that later earned the region the names “the little (Soviet) West” or the “inner abroad of the Soviet Union.”

Architecture in the Soviet Union was dependent on political patronage and coordination. Even in this respect, however, change was palpable, as younger architects began occupying leading positions in architectural management in the 1960s. In 1962, Gediminas Valiuškis, a modernist and innovator, was appointed Senior Architect of the City of Vilnius, and remained in this post until 1988.

It could be said that the seeds of modernism planted in the late 1950s began to blossom into beautiful flowers by the late 1960s. On the other hand, architecture as never before became dependent on the construction industry and the typical designs and standardization that were the main aim and centerpiece of an entire decade. “Banal modernism,” or mass-produced residential housing and standardized designs, undoubtedly brought about the greatest change in the urban environment of the 1960s.

Comments

Write a comment