The years from 1946 to 1953 are considered the most developed period of Soviet totalitarian art. It was during this time that a mandatory hierarchy of Soviet art was established. The most important artistic genres were considered to be public buildings, monumental sculptural works, official portrait and paintings on historic themes. Other genres that were less easily “verbalized” were pushed to the margins, including functional architecture (mostly residential homes, schools, nursery schools, and commercial and services buildings), genre painting, landscapes, and still lifes. What were considered the most prestigious examples of public architecture? The 1950 reconstruction plan for the city centers of Riga, Tallinn and Vilnius, authored in Moscow by architects L. Bogdanov and N. Kol, stated that “the new center of the [Lithuanian] republic should include the following public buildings: 1) the Palace of the Council of Ministers, 2) the Supreme Soviet (or Parliament) and the Lithuanian Communist Party (Bolshevik) Building, 3) the Ministry of State Security, 4) the Defense Ministry, 5) the Ministry of Posts and Communications, 6) the Opera and Ballet Theatre, 7) the Drama Theatre, 8) a cinema with multiple halls, 9) the Internal Ministry, 10) the Hall of State Institutions, 11) the State Republican Library, 12) the Hall of Labor Unions, 13) the Hall of the Intelligentsia, 14) the Palace of the Soviet Army, and 15) a monument to the Great Patriotic War.”

Only the most important public buildings were individually designed, whereas functional buildings (residential buildings, dormitories, industrial facilities) were to be designed using standard projects provided by the Moscow Planning Institutes (a process that was called the “local tethering” of a project). The most important and prestigious architectural projects were to be located in the capital. Though the Government Palace was never constructed, Vilnius did see the completion of several administrative sites of significance to the entire republic that were fully compliant with the standard designs imposed for such buildings throughout the Soviet Union. In addition to administrative (government) and symbolic (representational) buildings, an important place in the field of public architecture was also accorded to so-called “cultural-domestic” and “sanitary-hygienic” building complexes that had to reflect the “Party’s concern for the Soviet man.” Many new constructions were devoted to mass recreation or sports. Among the traditional sports halls and stadiums adorned with socialist realist sculptures, stand out in terms of both architectural scope and ornamentation were the prestigious Žalgiris Sports Complex (designed by architect E. Tamoševičius in 1954), complete with a stadium and swimming pool, in Vilnius, and a stadium planned for Kaunas which was never built. Some recreational architectural projects, such as the sanitariums built in the resort town of Druskininkai, were also unique in their level of luxury and decor among the larger group of newly constructed hospitals, clinics, and spas. Public saunas were also important new facilities in smaller cities and towns.

New railroad station buildings with adjacent public squares in Vilnius and Kaunas, and a new airport in the capital were called the “entrances” or “gateways” to Lithuania’s socialist cities. Special symbolic ornamentation was also planned for rebuilt bridges in the city centers of Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda.

The new hierarchy of buildings was also clearly reflected in the architecture of educational institutions. The most expressive examples of designs mirroring the structures of palaces and classical decor through the use of porticoes were the Vilnius Pedagogical Institute (designed by A. Kolosov, G. Rippa, and E. German in 1955), the Electronic Mechanics Technical School in Vilnius, and the M. K. Čiurlionis School for the Arts, also in Vilnius. The mass construction of 8-year or secondary schools, meanwhile, followed standardized designs for 2-4 story buildings used throughout the Soviet Union.

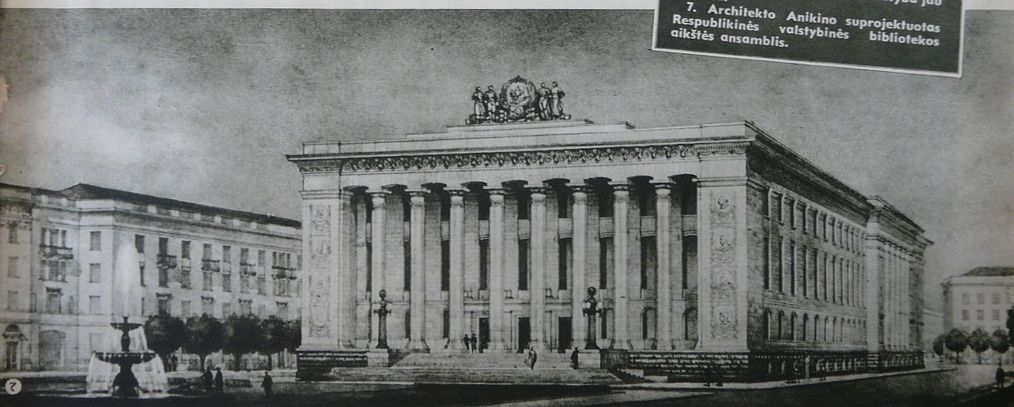

The style of cultural facilities and buildings in Vilnius was dictated both by the capital city’s status as well as the symbolic “triad” of cultural buildings adopted from Moscow that called for an opera house, a representative library, and an ornate cinema house. The design competition for and construction of an opera house in Vilnius dragged on for some time. The implementation of the winning proposal by architects A. Lukošaitis and J. Peras, drafted in 1950, encountered complications, though the site along the Neris River had already been selected. The Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre eventually arose in the same location, but based on a new design, only in 1974. The absence of the Opera House was subtly made up for by the Russian Drama Theatre, a building placed, despite construction restrictions imposed at the time, on the edge of a city block in central Vilnius. Less important spaces in the capital city were filled with buildings constructed to standardized specifications for cultural facilities, including the Railroad Workers’ Cultural Hall, the Vilnius Cultural Hall, and several cinema houses. A common, and virtually mandatory, feature appearing on the façades of new cultural buildings was a series of porticoes. The cultural hall in Naujoji Akmenė, complete with an ornate interior, became a symbol of this new wave of cultural halls.

Comments

Write a comment