Graphic design projects involved various objects, from packaging, boxes, and trademarks to advertising notices and posters, labels, or simple factory brochures. In the Soviet years, these types of design projects were relegated to the category of "industrial" or "applied graphics," "artistic construction," or "technical aesthetics," or were sometimes known by the rarely used terms "advertising" or "commercial graphics."

Graphic design projects were created by so-called "artist-constructors" receiving commissions from various ministries or the "Dailė" network of arts workshops, offices, or specific enterprises. The overall evolution of the design field in the Soviet system – and perhaps even artistic quality in general – was determined by decrees, rules, and resolutions "handed down" from above, as well as by priorities adopted by various commissions and councils. Graphic design was a creative field that existed between industry and art and between the technical and the aesthetic, marked by constant shortages of everyday products as well as modern showcase projects displayed at various exhibitions. Moreover, the field depended greatly on the initiative or inactivity of leaders and institutions and their policies. All of this transpired within the overarching context of a socialist economy, where the rules of competition, marketing, and advertising did not apply and where the functions of graphic design objects were never entirely clear:

While advertising may have a purely commercial purpose in the capitalist world, i.e. trying to push a product by any means possible, the purpose of socialist advertising was to provide objective and correct information about a product, its characteristics, and utility; it was meant to "suggest and advise," not "push." Jonas Urbonas, „Į kiekvienus namus ateinantis grožis“, Literatūra ir menas, 1968 02 17, p. 2.

In addition to propaganda texts about industrial graphics, artistic design, and the significance of advertising, there were also discussions about rhetorical questions that reflected the realities of the day: what could possibly be advised, much less advertised, when better quality products were being snatched up so quickly that most store shelves were always half empty?

A discussion of Soviet-era Lithuanian graphic design is made all the more difficult because of the fragmented state of information available about the period, with many archives destroyed or disbanded and surviving collections still in need of cataloguing. Any account must therefore begin with individual stories, a review of the period's most important institutions, their operating principles and the artists who worked for them, and with specific examples of graphic design using contemporary sources and eye witness accounts.

The renewal of Lithuanian graphic design was encouraged by several factors, including the modernization processes that began in the latter half of the 1950s; increased industrial production and a growing assortment of products; the "Art into Life!" program; and the Cold War's race to modernity (recalling Nikita Khrushchev's assertion that "We too have such things."). One of the keywords of the era "Tara" (Lithuanian for container or packaging), the simplified name given by artists working in the design field for their place of employment, the Experimental Package Design Bureau. The importance of this institution, as well as the specific circumstances imposed on graphic design, is revealed in the words of Kęstutis Gvalda, a long-time employee of the Bureau:

I don't know who came up with the idea to establish 'Tara', but it was a miracle. […] Though the name itself was horrible - students laughed at, it became a curse word. Tara ('container'), labels – this was the worst humiliation, but artists still went there to work. Everyone wanted to eat, so they went and paid no attention to anything. Interview with Kęstutis Gvalda, recorded by Karolina Jakaitė, December 16, 2009.

The initiative to open a specialized agency for container and packaging design was born in 1961, a time reviewed in the memoirs of the Bureau's founder and first director, Antanas Morkevičius:

At the time, there was a great urgency to increase exports of all types of goods, requiring artistically designed and modern containers and a very large amount of accompanying documentation (prospectus, instructions, posters, etc.) and advertising material in various foreign languages. So by late 1961, I was tasked with founding the Experimental Package Design Bureau. Antanas Morkevičius, „Tarp dangaus ir žemės“, in: Lietuvos medienos pramonė: nuo ištakų iki 2000 metų, Vilnius: Homo liber, 2001, p. 132.

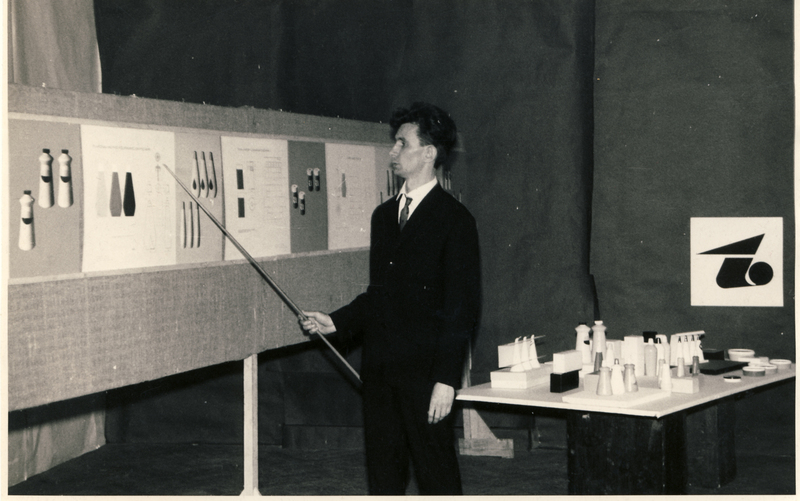

In 1963, a Container and Packaging Design Department opened as part of the Lithuanian SSR Regional Economic Council's Central Planning and Design Bureau, employing 8 artist-constructors. The official opening date of the new Bureau, however, is considered to be June 9, 1964, when the Soviet Lithuanian Council of Ministers State Academic Research Works Coordinating Committee approved the establishment of the self-financed Experimental Package Design Bureau, which became the most important center of graphic design creation, production, and promotion in Lithuania from the 1960s to the 1980s.

It should be noted that other institutions were also active in advertising graphics both prior to the Bureau's emergence and after 1964. These agencies included the Lithuanian SSR Art Fund (Dailės fondas), which received commissions for graphic design projects for production by the "Dailė" art workshops in Vilnius, Kaunas, and Klaipėda, and an advertising department that operated in Vilnius from 1973 as part of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, overseen for many years by Rimantas Žilevičius. Some government ministries had their own in-house design units, while larger enterprises had full-time artist-constructors on staff, as was the case with the Pergalė (Victory) confectionary plant and the Stumbras liqueur and vodka factory in Kaunas.

Comments

Write a comment