Although the concept of imagery was still evolving, it was already clearly present in theatre, focusing theatre professionals' attention on "the fluidity of image and movement." Dovydas Judelevičius, „Drąsa pasiteisina“, Tiesa, 1966 07 17. Early on, imagery was associated with modern set design, changes in fluid language, the redesign of visible reality and the effect of non-realistic images. Set designers began to avoid the portrayal of absolute truths and turned away from naturalism, heavy dramatism, pomposity, rigid representation, detailed narratives and superfluous or static objects.

Much like in Western European theatre, artists began to avoid painted sets, replacing them with objects that encompassed volume.

It was innovative to act without a curtain, decorations or historical costumes. Theatres that considered themselves to be innovative 'stripped' themselves bare, along with their costumes, in an attempt to throw off everything that weighed them down or restrained them or linked them to the past. A new struggle against naturalism began. Gražina Mareckaitė, „LTSP Valstybinis jaunimo teatras“, in: Lietuvių tarybinis dramos teatras: 1957–1970, sudarė Algirdas Gaižutis, Vilnius: Vaga, 1987, p. 76.

This was how theatre critics of the day described the changes. Designers, meanwhile, recalled that:

We attempted to implement the entire artistic concept of a set's design so that decorations <...> would not overwhelm the actor, but would rather elevate him, helping to reveal his thoughts and the subtext of the piece. Jonas Surkevičius, „Teatro dailininko šiokiadieniai“, Literatūra ir menas, 1960 12 10.

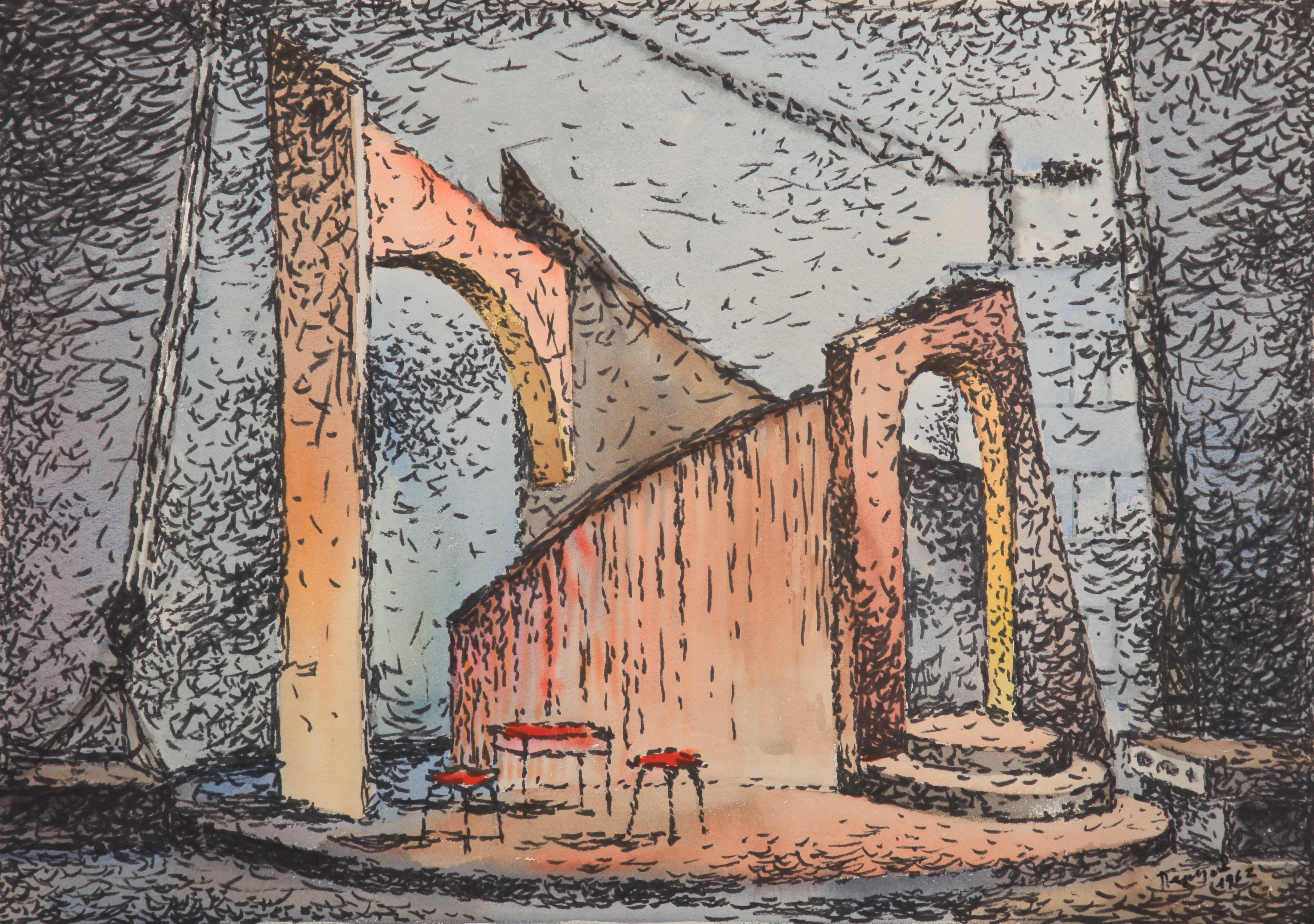

Not coincidentally, actors found themselves without their usual supporting objects (tables, chairs, sofas or closets), while production creators and audiences alike were encouraged to grow accustomed to contemplate and understand their modern, dynamic and paradoxical world in an environment of new forms.

The so-called "thaw" period saw the return of the understanding that "theatre happens when action replaces the plot and the narrative, and when the stage yields to movement determined by the trajectories of the clashes, battles and physical encounters between the play's heroes." Патрис Пави, Словаръ театра, Москва: Прогресc, 1991, p. 63. Theatre liberated itself from the theory of conflict avoidance. More and more, theatres were drawn to new technologies and methods of expression that could enrich the nature of a dynamic and conflictual era and expand the concept of imagery.

Set design in the 1960s was taken over by young theatre artists who promoted minimalism and light, moving sets, particularly on the stages of dramatic theatres. Basing their work on the universally relevant content of modern dramatic works, these artists abstracted shapes and simplified compositions. The idea of man as the central focus arises (as in the collection of poetry by Eduardas Mieželaitis entitled Žmogus [Man]). Man was seen as constantly changing and improving his world, seeking dialogue with others, with society and with history. As a result, artists began to create set designs emphasising a central space comprised of circular areas, platforms, steps and abstract shapes in an attempt to portray the imagery of new heroic personalities as well as everyday man.

Surkevičius and Jankus, already established set designers, and Arūnas Tarabilda, who came to theatre from the graphic arts, applied bold design solutions and used symbolic imagery. The productions of Balys Sruoga's Apyaušrio dalia (Fate Before Dawn) in 1956 at the State Academic Drama Theatre and Juozas Grušas' Herkus Mantas at the Kaunas State Drama Theatre in 1957 mark the dividing line between two periods in post-Stalinist theatrical art – between the realistic, illustrative set design employed up to this time and the non-realistic set design widely used thereafter.

Comments

Write a comment