If not for the fundamental changes brought on by the 20th and 21st Congresses of the Soviet Communist Party, the applied arts would not have experienced the renaissance of recent years [...] Indeed, where would the applied arts be without the grandiose construction of residential buildings in our country, if millions of Soviet people would not have received new apartments, if we had not taken care of the domestic lives of Soviet people? It goes without saying that the decorative arts could never have developed at such a pace. Декоративное искусство СССР, 1961, Nr. 6, p. 4–5.

An artistic foundation will bring spirituality to work, enhance everyday life, and refine man. USSR Communist Party Platform

When did the process of modernism begin in the Soviet applied arts? Paradoxically, it is difficult to define a firm boundary that marks a change in the aesthetical understanding that resulted in the appearance of innovative ceramics, textiles, glass and interior furnishings. Moreover, despite the ideologization of art, Lithuanian artists created works of art throughout the Stalinist period not only for official audiences, but also for themselves – fostering the values they had learned as students. Later, such works as the tasteful ceramic vases created by Liudvikas Strolis and Jonas Mikėnas, glass pieces by Stasys Ušinskas, and the post-war woven carpets of Juozas Balčikonis would be taken from personal collections and exhibited as proof of artistic resistance against the oppression of the ruling regime.

Browsing through the pages of the first editions of Декоративное искусство СССР Decorative Arts of the USSRДекоративное искусство СССР (Decorative Arts of the USSR) was a magazine devoted to the applied arts and design that, even under harsh censorship, published articles not only about Soviet applied arts and design, but also about trends in Western avant-garde art, design and architecture. The first, experimental edition was published in 1957, and the magazine continued to run periodically from 1958 to 1993. In 2012 the publication was revived by the Russian and CIS Modern Art Fund "Artprojekt" simply as Декоративное искусство (Decorative Arts) (full official name: Декоративное искусство стран СНГ (Decorative Arts of the CIS countries). (Decorative Arts of the USSR), first published in 1957, we would be surprised by the innovative spirit emanating from a magazine that had become the standard bearer of a new style. When did the rational, aesthetically pleasing form promoted by this magazine become the norm?

Usually, historical and political events are the basis for establishing the start of a new era. It is very likely that the inner desire for a more innovative artistic environment began forming during the peak years of the so-called Stalinist triumphalist period. However, the actual opportunity for change came later, after the fall of the Stalinist regime and with the liberalization of Soviet political life. It was then that the Communist Party published its famous decrees on "architectural ornamentation" (in a 1955 decree entitled "Removal of excesses in design and construction"), which led to a deluge of critique of so-called façade architecture Façade architectureFaçade architecture was a construction and building trend that emphasised excessively decorative façade elements that had little to do with a building's structure, incorporating elements such as columns, pediments, cornices, towers and balconies. This trend was prevalent in 19th and 20th century periods (during the Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union, and in the immediate post-war years in Lithuania) that emphasised the ideological and representational roles of architecture., and the purposeful development of a new aesthetic in the art world.

Creators of applied art became part of the push for the modernization of domestic life, while their political overseers took up the slogan "art for domestic life." Appealing, familiar objects and an aesthetically pleasing everyday life became essential for a country that had healed the wounds of war. For the first time since the war on a national scale, Soviet functionaries began viewing the people's everyday surroundings as a determining factor of their quality of life and a critical piece of personal development.

There then followed a series of well-known historical events. The 20th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1956 condemned Stalin's cult of personality and established guidelines for the modernization of society. Positive trends in the applied arts were initiated by the First Congress of Soviet Artists in Moscow in 1957, which criticized the previous Stalinist culture and issued new challenges for the art world. The famous Soviet applied art historian Alexander Saltykov (1900-1958) addressed the Congress in a report entitled "On Decorative Art," in which he criticized the flawed "view of decorative art from the perspective of the fine arts." An exhibition of applied art (with the participation of 19 Lithuanian artists) was organized to coincide with the Congress.

Nikita Khrushchev's reforms have been referred to historically as the "thaw" period, a term borrowed from Ilya Ehrenburg's Ilya EhrenburgIlya Ehrenburg (1891–1967) was a Russian writer and poet. During World War II, Ehrenburg worked as a journalist and served as an author of official propaganda for the headquarters of the 3rd Byelorussian Front, becoming famous for his appeals that fuelled the genocide of civilians in Soviet-occupied Königsberg. 1954 novel The Thaw.

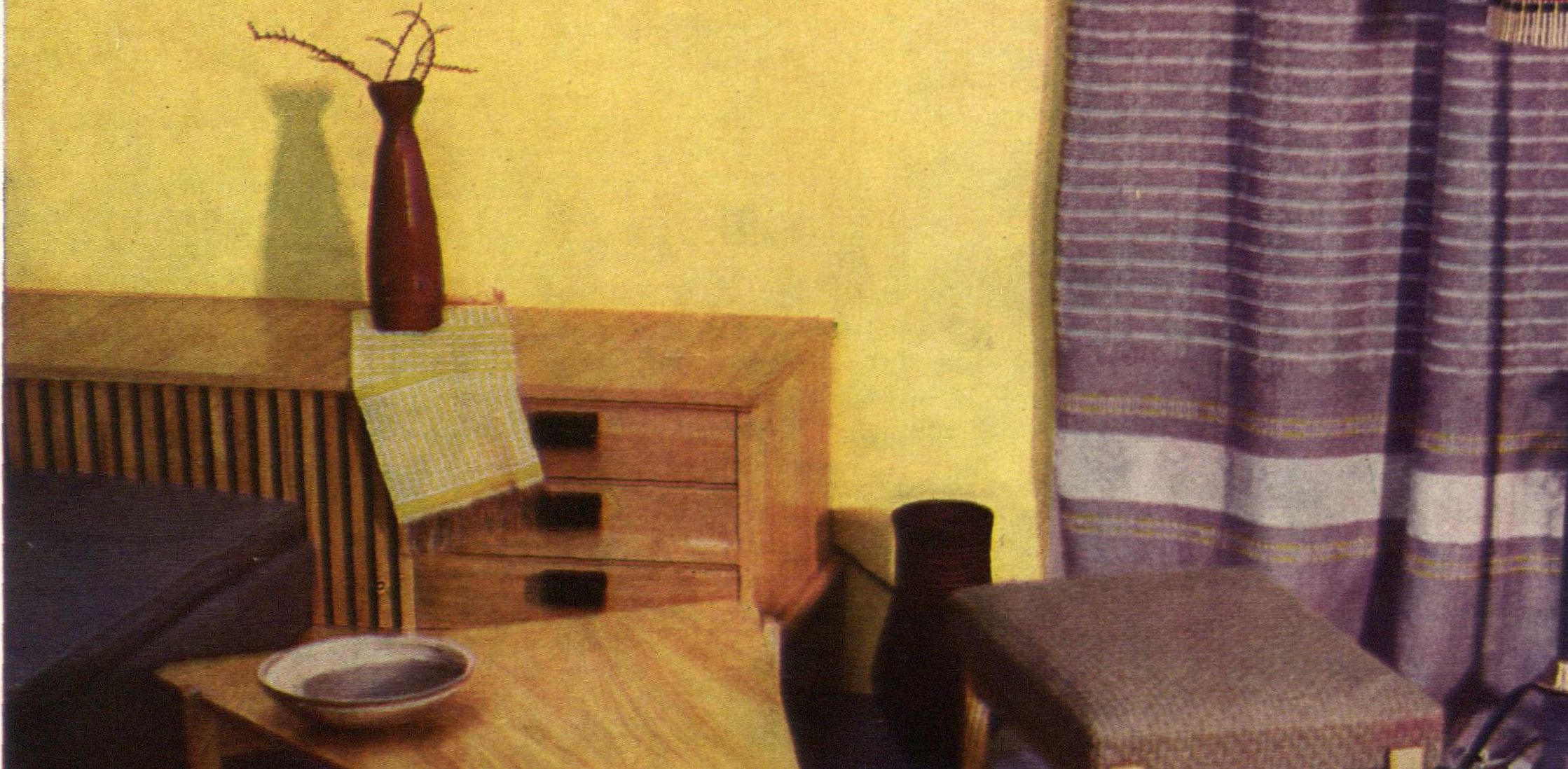

Architecture was first to liberate itself from the historical pomposity of the Stalinist era. After the decrees adopted in Moscow between 1954 and 1957 to expand urban boundaries and begin construction of concrete-paneled residential buildings, the village of Novye Cheryomushki, near Moscow, transformed into one large construction site in 1958, becoming the first area to see the "block" housing neighborhoods that would spread throughout the Soviet Union. The first concrete-paneled five-story apartment buildings, called "Khrushchyovkas", were constructed in Vilnius in 1959. Once the block-style building boom began in earnest and the urgent need for cheap furnishings arose, a new battle began over the aesthetics of domestic life.

Propaganda espousing a new, modern lifestyle found fertile ground in the ideas of scientific and technical progress, the post-war recovery in Soviet industry, and the developing space program. Official propaganda was accompanied by a cult of youth, enthusiasm and dynamism. As censorship eased and the "Iron Curtain" parted slightly, society embraced feelings of spiritual revival and openness to new ideas.

Comments

Write a comment