During Tara's first decade of operations, the Bureau created 18,000 consumer packaging projects, five hundred trademarks, one hundred posters, and prepared 1,890 publications for print. These figures could be doubled for the Bureau's entire existence, from 1964 to 1991, and in some instances even tripled – but quantity was not the most essential consideration.

The quality of design projects produced at the Bureau and the professionalism of its artists is perhaps best judged by the modernity of their artistic language, the long list of exhibitions and awards won at biennial shows in Krakow, Warsaw, or Brno, by publications in the local press and such specialized trade publications as Dekorativnoe iskusstvo SSSR, Tekhnicheskaya estetika, or simply by the sincere reviews written by consumers themselves. Industry professionals reserved particular praise for brand designs and posters produced by the Bureau, but an equal amount of creativity was also needed to design new labels, advertising brochures and boxes.

We might begin with the smallest examples of graphic design projects – labels. Labels were very regularly redesigned or updated, or reprinted after supplies of one series had been exhausted, changing paper types, formats, typefaces, or colors. In 1970, companies overseen by six different ministries and agencies were responsible for label production in Lithuania. Tens of thousands of labels were produced over the course of several decades. Each new draft label design had to be approved at meetings of the Bureau's Arts Council, but the surviving examples of label designs varied in artistic quality and names were often reused, so that it is not always easy to establish authorship or dates of creation.

When artists of the Tara Bureau entered the label field in the mid-1960s, however, label designs became noticeably more professional – more bright and colorful, with better coordinated colors, more variation in composition, and the use of more modern typefaces. At the initiative of its designers, the Bureau began producing thematic label series with more unified styles displaying the creative styles of a given designer.

A label's artistic choice must not only advertise, it must also inform. Birutė Matijošaitytė, „Unifikuota vaisių-uogų ir daržovių konservų etikečių sistema“, in: Tara. Reklama, 1968, Vilnius: Eksperimentinis taros ir įpakavimo konstravimo biuras, p. 15.

Such was the message carried by the Bureau's trade journal, Tara. Reklama, in 1968. If we analyze examples of Lithuanian beverage designs in the 1960s and 1970s, we can better see the informational role played by labeling. One quick glance at beverage labels reveals a recurring theme of naming products with Lithuanian place names from nature, cities, resorts, lakes, and rivers: Palanga liqueur, Puntukas sparkling wine (named for a landmark boulder in north central Lithuania), Rubikiai berry wine, Žuvintas flavored wine, Nemunas Lithuanian gin (after the country's longest river), or Anyščių šilelis mead, named after a famous Lithuanian poem. The brands emerged as references to, or echoes of, ethnographic expeditions that become part of Lithuanian history and local traditions of environmental and ethnographic research.

Label concepts changed and adapted to bottle designs, which were also being updated in the 1960s to create original approaches and shapes for each beverage type. Custom-designed and limited-edition packaging was introduced so that companies could showcase their product lines. A stand out in this effort was the Stakliškės factory, famous for its Lithuanian mead recipes and souvenir packaging designs. Advertising texts and visual representations of these beverages emphasized a link to Lithuanian antiquity, glorified ancestral military campaigns (using product names such as "Bočiai" – Ancestors, "Pilėnai" – the site of a famous battle against the Teutonic Order, or "Žalgiris" – the Lithuanian name for the 1410 Battle of Grunwald), historic Lithuanian sites (Prienų šilai - the Forests of Prienai) and place names (Dainava).

Another wonderful example of labels performing an educational role was an eight-label series produced for Anykščiai Wines featuring historic imagery of Lithuanian cities, castles, and estates. Romualdas Svaškevičius, a Tara designer given the commission to design a showcase series of labels for natural Lithuanian wines, recalls the engravings depicting historic Lithuanian cities, manor houses, and castles that he selected for the different beverages. On the label for the Anykščiai Cherry Wine, for example, we see a gold framed lithograph of Napoleon Orda's 19th century Biržai Castle; on the Apple Wine – an image of the Radvila (Radziwiłł) family manor in Kėdainiai; and on the Mountain Ash Berry Wine, Tomasz Makowski's depiction of the city and castle of Trakai in the 17th century.

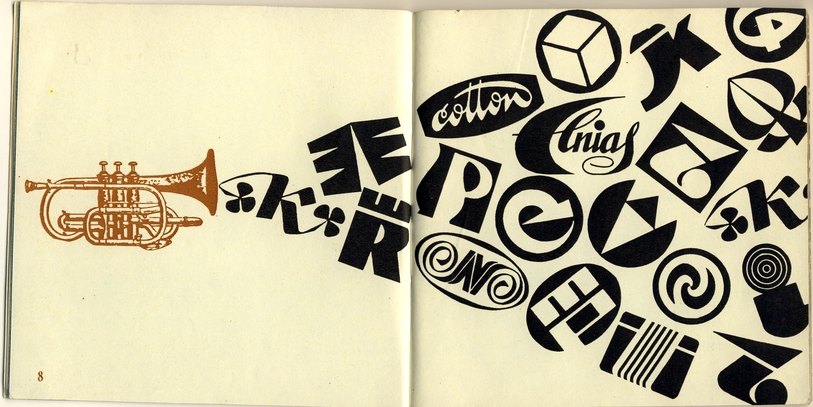

The modernization of label artistry was often determined by changes in typefaces and brand designs. While the 1950s saw the predominant use of inscriptions incorporating folk art motifs and ornamentation, artists in the 1960s sought to create unique fonts for each beverage to better reflect its type and name to shape a recognizable composition. This trend was well illustrated by Vladas Lisaitis' label designs for "Piliakalnis" (Castle Mound), and Kostas Katkus' labels for such beverages as "Pipirinė" (Pepper Brandy), "Medžiotojų karčioji" (Hunters' Bitters) and "Anykšta".

Comments

Write a comment