During the Soviet era, the Graphic Art Division of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union was a closed and privileged community. The close-knit cooperation among its artists and the unique development of graphic art in general was primarily a factor of the technical considerations specific to this field of art.

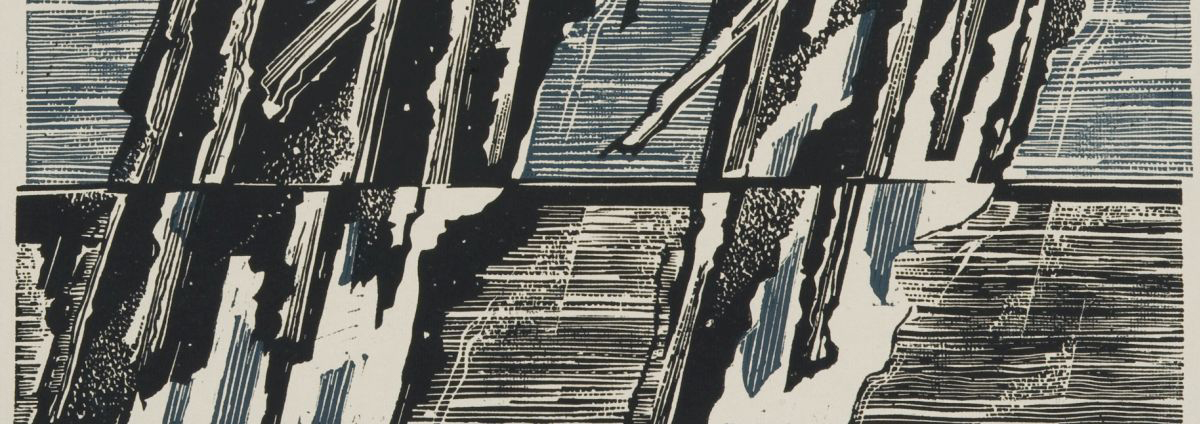

Embossing using sheets of coarse wood or linoleum predominated in Lithuanian graphic art in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s. The continuation of rural folk art traditions happened to coincide with the official government policy of promoting the national identities of the Soviet Union’s republics. Over time, however, artists grew tired of the folklore style and they sought out new techniques. The 1970s saw an increase in the use of etching and lithography, as well as silkscreen and multicolored printing. Toward the end of the Soviet period, graphic artists began to favor darker tones rendered using complicated chemical (aquatint) or physical (mezzotint) methods.

Graphic artists tended to work in shared studios and workshops. Only the most prominent and officially revered artists were able to acquire all of the necessary equipment and materials to stock their own, private studios. An experimental graphic arts workshop was established in Vilnius by the Artists’ Union in 1968, on Grybo Street in the Antakalnis neighborhood. In 2000, the studios were moved to Latako Street and reorganized as the Graphic Art Centre and the “Kairė - dešinė” (Left-Right) Gallery. The new institution’s active program and presence contributed to a flourishing of graphic art in the 21st century. Artists, especially instructors, also often availed themselves of the printing presses housed at the Lithuanian State Art Institute, assisted by experienced technical specialists. At night, workshops and printing facilities were locked behind heavy iron doors to ensure against anyone suddenly getting the idea to print dissident publications or leaflets, but artists were always somehow able to find their way back inside for afterwork celebrations. They were able to see the work being done by their colleagues, as the creative process was fairly open and accessible. Partly for this reason, less strict official regulations were applied to printmaking than for painting, and graphic artists were also less prone than painters to develop their ideas in secret.

Prevailing trends in graphic art were clearly discernible at special exhibitions and in exhibit catalogues. Starting in 1968, Lithuanian graphic artists participated in the graphic arts triennials held in Tallinn, Estonia, and later at biennial shows in Kraków, Poland and Ljubljana, then part of the former Yugoslavia. The government would turn a blind eye when artists took the initiative to send their ex-libris to international exhibitions. Under the Soviets, print runs of Lithuanian graphic artwork albums as well as publications featuring the prints and engravings of individual artists were consistently high. Glavlit, the state’s central censorship agency, began monitoring these publications and book illustrations from the mid-1960s onward.

Because of the specific nature of the production and dissemination of graphic art, the field’s overall development can only be compared in part to trends occurring in painting. The pop art prints of younger graphic artists of the 1970s have much in common with the works of the renowned “Foursome” group of Lithuanian painters, while the aquatint blackness and otherworldly creatures of the 1980s approximates the paintings of the “Fivesome”, and the revival of engravings inspired by folklore traditions during the time of the “Sąjūdis” national reform movement shares elements of neo-expressionism.

Technical aspects of graphic art shape the imagery and the content of any given work. In postmodernism, these are conceptualized. Mechanical copying, required for the transfer of a sketch onto a printing plate (or “cliché”), becomes part of the creative process in the form of imagery references. The close link between printmaking and book illustration fostered graphic art’s unique relationship with language and words. Series of engravings that convey a narrative developing over given period of time are also quite suitable for artistic research.

Comments

Write a comment